Dr Séverine Caluwaerts, an obstetrician from Belgium, has worked in MSF’s Khost maternity hospital in eastern Afghanistan nine times in the past six years. Séverine was there to witness the first baby born on the ward, and again earlier this year when the team celebrated its 100,000th birth. She remembers the morning a woman was brought to the hospital, unresponsive and bleeding profusely.

“She came to our hospital after delivering her 11th child at home. She started bleeding during the night, the placenta still stuck inside her. She should have received care hours ago, when the bleeding first started. But it was too dangerous to travel at night. Her family had no choice but to hold on for a few more hours until first light, when they were able to drive to hospital.

As she is rushed through the gates, pale and completely breathless, I take one look at her and think she is already dead. But still, we have to try and save her.

We rush her into the stabilisation room – I can’t feel a pulse and her blood pressure is non-existent. We try to resuscitate her. I plan to stop in 20 minutes – I can see it’s no use. She’s already gone.

Aurelie Neyret/The Ink Link/MSF

This is so sad, I think to myself; she will die under my hands, leaving 11 children behind at home. When a mother dies it's not just her life, but the lives of her children and the life of her husband that are shattered too. Everybody is affected. A mother, a woman, has a huge impact on the family.

Then, suddenly, a very weak pulse. We give her a blood transfusion, then a second and third, until four units have been pumped into her. Her blood pressure starts to rise and we rush her into the operating theatre. She is bleeding profusely. We have no choice but to remove her uterus.

Miraculously, she starts to improve. She starts to stabilise. The bleeding slows, then stops. In the end, we give her 10 units of blood just to keep her alive.

She goes home five days later and I still can’t believe it. I never thought she would make it. But she survived – a fighter, like so many of the women I’ve met in Afghanistan.

This woman’s story is not uncommon in Khost. The extraordinary happens every day on the MSF maternity ward. I’ve been coming back to work in the hospital nine times since we first opened our doors in 2012 and it holds a very special place in my heart.

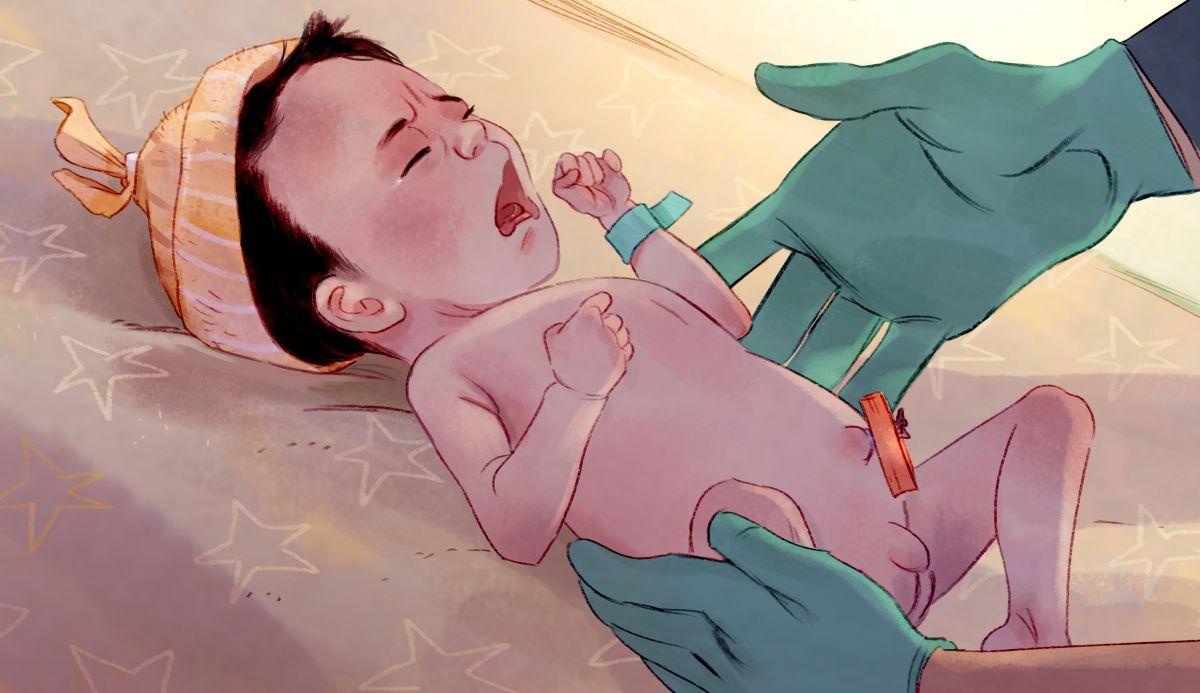

I saw the first baby born, and now 2,000 women come through our doors every month to give birth. Earlier this year we even celebrated 100,000 babies born here. It is MSF’s busiest maternity hospital in the world.

A hospital for women, by women

Afghanistan remains one of the most dangerous places in the world to give birth. When MSF first came to Khost province, we found that many women and babies were dying needlessly, simply because they could not get the medical care they needed. Back in 2012, there was a severe lack of qualified staff, and mothers and babies were dying of preventable and treatable conditions.

When we first opened we had 15 deliveries a day. That quickly climbed to 30, then 50. And now, on our busiest days, we have as many as 100 women giving birth in our hospital.

But MSF is offering more than just quality, free-of-charge care for pregnant women and babies in Khost. It’s a hospital of women, for women. Almost all of our team are female. This is incredibly important in this area of Afghanistan: there is a strict separation of the sexes which must be upheld, especially on a maternity ward.

From the moment they step through our doors, we want patients to feel at ease. It’s a place where families know their wives, mothers, sisters and daughters will be safe. Our Afghan colleagues feel responsible for their patients and treat them like family. They say things like, "Hey, my sister. I will take care of you." And quite often, they are actually family as our staff encourages their sisters and other relatives to come to deliver at the hospital too.

There’s a feeling of openness inside the ward: women can remove their burqas, they can show their hair, they can breastfeed their babies. This is because there are no men on the ward: it's women taking care of women.

Aurelie Neyret/The Ink Link/MSF

If you plant seeds, you will grow flowers

MSF is also one of the largest employers of women in Khost: we employ around 430 people, the majority of them women, many who had never had jobs before. We’ve hired female cleaners, nurses, midwives, nannies and doctors.

Many of our staff have families of their own and are often the primary caregivers. So that they don’t have to stop working, we opened a nursery at the hospital with free childcare. It’s great for us because we retain really valuable staff, but it also gives women the opportunity to keep on working, even when they have small children to take care of.

So many of our female staff are eager to learn new skills and gain qualifications: midwives become doctors; receptionists become midwives; cleaners become receptionists. That’s why it’s so wonderful to keep returning: I see the doctors I taught to do caesarean sections doing the procedure by themselves, confidently, only one year later, with no need for help from me. If you plant seeds, you will grow flowers and the occasional rose.

Aurelie Neyret/The Ink Link/MSF

We can’t save everyone

Despite our best efforts, we cannot save everyone. This is one of the hardest things about working in Khost. During my time there, I witnessed three women die in labour or from complications related to childbirth.

One woman, whose image will stay with me until I die, came to the hospital in May this year. I remember the date clearly because it was the day my grandmother died.

At 9.30 in the evening I received a phone call from one of my Afghan colleagues working the night shift in the hospital. A heavily pregnant woman had been brought to the hospital suffering from what they thought was a severe asthma attack. She was seven or eight months pregnant and expecting triplets.

When I arrived she was in cardiac failure. Her heart, not her lungs, was giving out. It was not pumping enough oxygen through her blood. By the time I saw her, she was gasping for air.

Aurelie Neyret/The Ink Link/MSF

We gave her drugs for her heart and called the anaesthetist. We needed to deliver her babies by caesarean section before we could begin resuscitation. But it was too dangerous for her to go into theatre – she could die at any moment on the operating table. It was a terrible choice – like choosing between cholera and the plague.

We decided to stabilise her and try again for the theatre in one hour, if the family agreed to a caesarean section. I went outside to discuss the options with her husband and mother-in-law.

While I was explaining the situation, she went into cardiac arrest. With the babies still alive, we needed to operate as quickly as possible, but there was no time to rush her into theatre.

I did the operation in my flip flops, that’s how quickly events changed. We delivered the triplets, but their mother died on the stretcher in the delivery room. We tried and tried to save them all.

The first two babies lived for half an hour. The third, I prayed, would make it, so that something positive would come from this misery. But she died 36 hours later.

I will never forget the moment we brought the husband in to see his wife. He collapsed in tears over her body. Everyone around me was crying, and I had tears in my eyes too.

But thankfully these moments are rare. The vast majority of women who come to us walk out of our doors healthy, with their beautiful sons and daughters in their arms.

Aurelie Neyret/The Ink Link/MSF

Hope for the future

Working in Khost has changed my life. It has been a real privilege to see the beautiful aspects of Afghan culture. I have met some wonderful, strong women who are trying to make a difference in their communities. We all have so many things in common, more than all of our differences. I felt this more than ever in Afghanistan.

I am so proud of the work MSF is doing in Khost: the hospital is offering real hope to the community, and our work across the country is having an impact on reducing the number of mums and babies dying during childbirth.

Perhaps that’s why so many women name their daughters Hila. It means ‘hope’; hope for a better future, for Afghanistan, for children and for women. Because they have hope, I also have hope that one day things will be better. Not yet, but one day. I have hope.”