Already struggling with measles and Ebola epidemics, DRC declared its first case of COVID-19 on 10 March; since then, the virus has gradually spread across the country. To reduce its spread, especially in its capital of 13 million inhabitants, Congolese authorities quickly put in place preventive measures, including movement restrictions, a partial lockdown of certain districts and the compulsory wearing of masks in public. They also raised awareness on protective measures such as handwashing, cough etiquette and physical distancing.

Despite these measures, however, cases continued to multiply steadily. Within three months, more than 4,500 people were confirmed to be infected with the virus – a likely underestimate given the limited COVID-19 testing capabilities within the country.

Faced with the danger posed by the new coronavirus, MSF quickly set up COVID-specific responses in all the areas where its teams work, in Kinshasa and elsewhere in the country, strengthening preventive measures, installing isolation spaces and carrying out health promotion and awareness-raising activities among communities.

"In Kinshasa, we quickly organised mobile teams to support 50 health facilities," says Karel Janssens, MSF head of mission in DRC. "Our teams have reinforced hygiene measures there, provided masks and handwashing facilities, and trained medical staff and community workers in infection prevention and control. The protection of health staff and patients was immediately our main priority."

More and more serious cases

A few weeks into the pandemic in DRC, MSF also started supporting Saint Joseph hospital in Kinshasa’s Limete health zone. Our teams set up a 40-bed treatment centre for patients with mild to moderate symptoms.

“From early May to early June, an average of 30 patients were treated at the centre each day”, says Janssens. “At the start of our response, most patients suffered from mild forms of the virus. But since mid-May, we have been receiving more and more patients in a serious condition. By 11 June, 14 of the 29 inpatients were on oxygen therapy.”

Jean-Pierre is one of the many patients admitted to Saint Joseph. After more than 10 days of treatment, he is getting ready to go back home.

“Before coming, I had headaches, aches and I was coughing”, he said. “I had taken medicine but there was no change. Encouraged by my wife and children, I went to Saint Joseph to have a voluntary test. When the results came out, I was admitted. After more than 10 days of treatment, I feel good. I had another sample taken for another test but I’m waiting for the results.”

As the country has only one laboratory to perform the tests for COVID-19, many people have to wait for days, and sometimes for weeks, before they receive their results. In Saint Joseph, more than 10% of patients had to wait more than two weeks to get those results. This situation is difficult for people with suspected coronavirus, and also for recovered patients, who cannot leave hospital until they receive the all-clear, despite the mounting pressure on hospital beds.

The hidden effect of COVID-19 on care

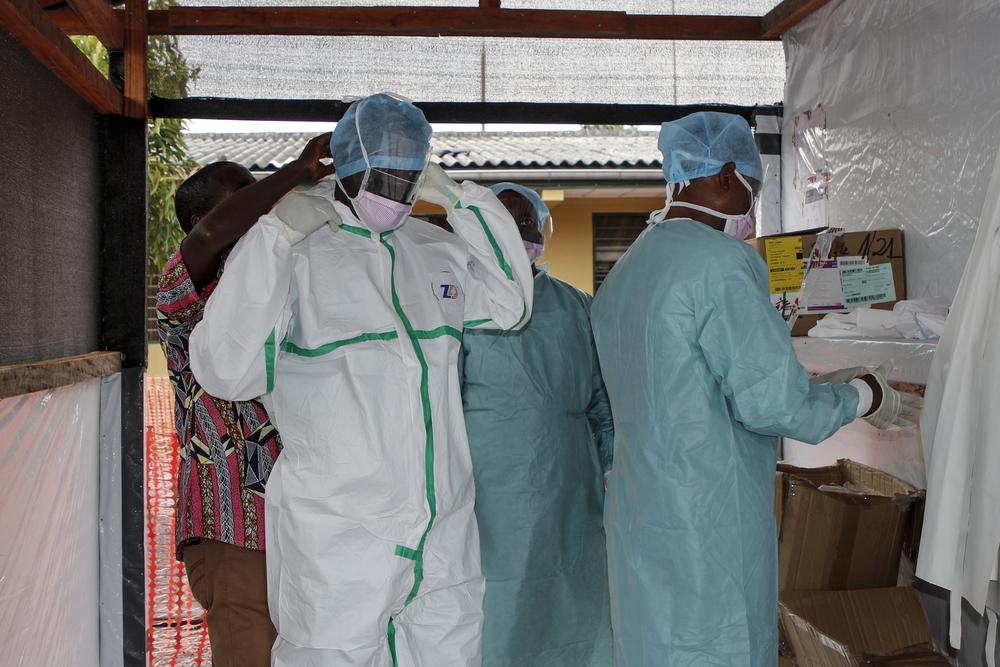

Medical staff dress with PPE (Personal Protective Equipment) to enter the high-risk area of the COVID-19 treatment unit at Saint-Joseph Hospital in Kinshasa (DRC). © MSF/Franck Ngonga

The low capacity for testing and the delays in communicating the results are not the only challenges posed by the COVID-19 response in the Congolese capital. Since the declaration of the pandemic, MSF teams have seen a marked drop in the number of consultations and admissions in the health facilities they support in Kinshasa, including in MSF’s centre for people living with HIV/AIDS, the Kabinda Hospital Centre.

"At the Kabinda Hospital Centre, the number of HIV consultations fell by 30 per cent between January and May,” says Gisèle Mucinya, medical coordinator at MSF’s HIV/AIDS project in Kinshasa. “And in Ngaba Mother and Child Centre, which we support, a 44 per cent drop in general consultations was recorded between January and April. It’s very disturbing." The same observation is made by Dr Rany Mbayabu, director of Kinshasa’s Mudishi Liboke private hospital. "Since March, consultations here have dropped by more than half, from about 250 to 100 patients per month. Our patients tell us that they are afraid of being contaminated by COVID-19 when coming in to consult. Others are affected by the difficulties of movement and the economic impact of preventive measures." This drop in medical attendance is a cause for concern for MSF teams. If patient numbers have fallen in facilities that MSF supports, which offer free healthcare and adequate protective measures, then they are likely to have fallen in medical facilities across the capital. As a result, many more patients may die of conditions that could have been prevented. The mortality rate linked to other medical conditions is expected to be much higher than that currently observed in patients with COVID-19.

"Many people fear they will be infected with the virus by going to health facilities deemed under-equipped with protective equipment, or they fear being isolated and stigmatised for a long time due to the delays in obtaining test results," says Karel Janssens. “This situation affects the care of sick people and the monitoring of their treatment, especially for conditions such as diabetes, tuberculosis, malaria and HIV/AIDS."

To help address this situation, MSF is notably advocating for health centres to be better supplied with personal protective equipment. "This would improve patients' confidence in going to health facilities and, in turn, strengthen efforts to contain the spread of COVID-19 while providing essential medical services," says Janssens. “Faced with a pandemic like COVID-19, and in view of the increase in respiratory infections that accompany the dry season, it is vital to ensure the proper functioning of frontline health facilities to prevent a further reduction in patients’ access to care."