As the worst Ebola outbreak in the history of DRC is entering its second year, the situation on the ground is concerning. In July, between 80 and 100 people were diagnosed with the disease each week. Uganda saw its first Ebola patients who had travelled from DRC in June, while Goma, a city of 1.5 million people, recorded its second case just this week.

Since last August, Ebola has infected over 2,600 people, and killed nearly 1,700. Approximately a third of Ebola-related deaths so far have been diagnosed post-mortem, while on average six days pass between the onset of the symptoms and the time a patient is admitted into an Ebola treatment or transit centre – a time during which a patient’s conditions deteriorate and the virus can be spread to infect others.

It is clear that the response has so far failed to control this epidemic, despite having tools at its disposal that were either unavailable or severely limited in previous Ebola outbreaks,such as an investigational vaccine and developmental treatments.

Since the beginning of this outbreak, insecurity has been mentioned as a significant challenge for the intervention. North-Eastern DRC has been an area of active conflict for the past quarter century and is rife with armed groups.

But neither the fear induced by this highly lethal, little-understood disease, nor the pre-existing tension in the area can alone explain the response’s inability to win the local population’s participation to the effort. The overall approach of the Ebola intervention has to be questioned and improved.

Set up as a “parallel system”, Ebola treatment and transit centres are distinctly separate from the healthcare facilities people are familiar with. As a result, they appear shrouded in mystery; seen as places where people go to die, once they’ve been separated from their families. Tellingly, 90% of the patients admitted over the course of the year have tested negative for Ebola and likely suffered from another illness. However, these centres lack the capacity to provide quality, individualised care during the waiting period for the Ebola tests results. This has undoubtedly hampered communities’ acceptance of such facilities.

MSF’s activities in this volatile region predate the Ebola epidemic and our teams witnessed and responded to recurring crises due to violence, endemic malaria, outbreaks of measles or cholera. However, the massive mobilisation of resources associated with the response marks a striking contrast to the neglect this region has suffered from over the decades. This adds to the widespread belief that the Ebola intervention’s priority is not the population’s best interest.

![msf251938_medium.jpg Awareness-raising and information activities are essential to win the trust of the population and make them understand the challenges of rapid care.[ Alexis Huguet ]](/sites/default/files/msf251938_medium.jpg)

Awareness-raising and information activities are essential to win the trust of the population and make them understand the challenges of rapid care.[ Alexis Huguet ]

As such, the response must urgently adapt to the needs and expectations of the population, including in terms of preferences in the provision of healthcare, if we are to gain control of the epidemic. This is why MSF is working to integrate its Ebola-related activities into local health centres and hospitals, looking to encourage early reporting of symptoms and to facilitate early identification of suspect cases. The indications are positive: in July, 20% of the patients admitted to an Ebola treatment centre in Beni were referred from a health centre supported by MSF – this is a higher percentage than that of patients referred from Ebola transit centres.

Lastly, MSF joins the call of many experts who recommended expanding access to the investigational vaccination being used in this response. Over 170,000 people have received the vaccine so far through a “ring vaccination” approach which targets the contacts of confirmed Ebola patients and frontline workers, but access to vaccination must be expanded to cover all the population at risk.

Such steps are needed urgently if we are to prevent the epidemic from lasting another year.

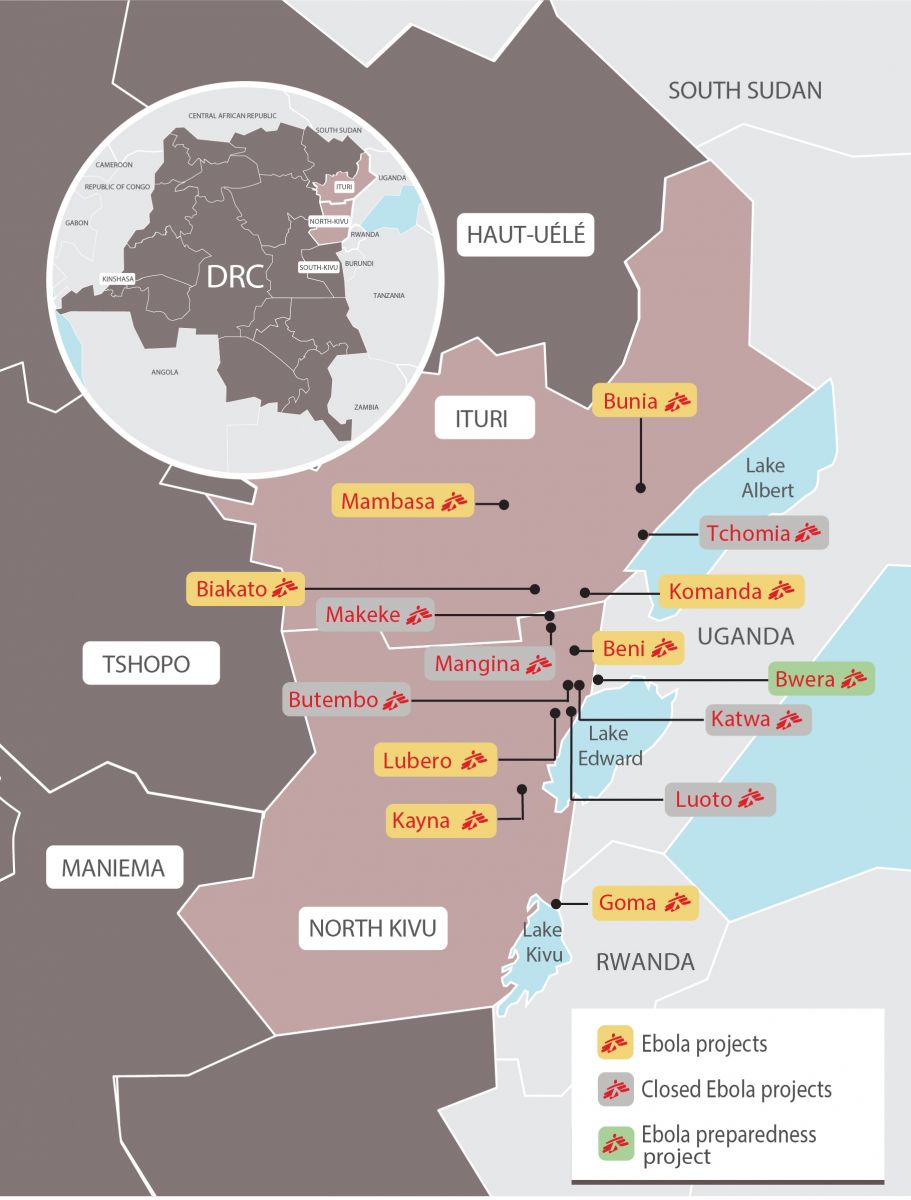

Our teams are currently working to support the local healthcare infrastructure in cities such as Goma, Beni, Lubero and Kayna in North Kivu and Bunia, Mambasa and Biakato in Ituri. Support covers activities like primary healthcare, triage, isolation, infection prevention and control, water and sanitation, referrals and health promotion. We also support a 34-bed treatment centre in Bunia and a small ETC in Goma, while finalising the construction of a larger, 72-bed ETC in the city.