Every two to three years, measles outbreaks affect tens or even hundreds of thousands of children in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Last year was no exception, with more than 148,600 cases and 1,800 deaths reported. How can this recurring emergency be explained? And, above all, how can we put an end to it?

When one speaks of an emergency in DRC, the problem of measles is rarely the first image that comes to mind. Yet this disease regularly wreaks havoc on young children—the main victims of measles—and has been the primary reason for intervention by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) emergency teams in DRC for years.

"We have five emergency teams mobilized almost around the clock to respond to the various measles outbreaks throughout the country. But as soon as we put out a fire here, it flares up on the other side,” says Dr. Louis Massing, MSF’s medical referent in DRC. “In 2022, we carried out 45 measles-related emergency interventions; that’s more than three-quarters of our emergency response in DRC.”

The largest measles outbreak ever documented in DRC occurred between 2018 and 2020. At that time, nearly 460,000 children contracted the disease, and 8,000 of them died. Large-scale vaccination campaigns had been organized by the health authorities, supported by international partners such as MSF, enabling the number of cases to be drastically reduced by 2021.

"But last year, nearly half of the country's health zones were once again in an epidemic situation,” laments Dr. Massing. “And it’s not over. In January 2023 alone, close to 20,000 suspect cases of measles have been notified in DRC and our teams have already responded to measles outbreaks in Tshopo, Maniema, South Kivu, North Kivu, Lomami and Lualaba provinces.”

“There can be no weak links”

Measles is one of the most contagious disease in the world. Fortunately, a vaccine exists and offers almost complete protection when a person is inoculated twice. Since a person carrying the virus can infect up to 90 per cent of the unvaccinated people around him or her, ensuring maximum vaccination coverage is vital. This requires massive investments in routine vaccination, surveillance and catch-up campaigns.

“The fight against measles is like a chain around the virus: if one link is broken, the virus can escape,” says Dr. Massing. “First, the country must ensure that sufficient quantities of vaccine are available to avoid stock-outs at health facilities. Then, it is necessary to ensure that the vaccines are delivered to the health facilities and that they have an efficient cold chain to keep the vaccines stored in good conditions. It is also necessary to have staff on site to vaccinate children during consultations, and for families to have the economic and physical means to go there. Finally, regular catch-up campaigns must be organized to protect children who fall through the cracks… Given the virulence of measles, there can be no weak links."

Unfortunately, many elements of that chain are weak in DRC, and this situation is further aggravated by security constraints, geographic challenges to reach many areas, and the country’s high birth rate, with over 2 million babies born every year who need to be protected from the disease.

As a result, despite emergency campaigns conducted during each outbreak, immunization coverage remains insufficient. While coverage estimates can vary widely from one source to another, the latest estimates from UNICEF and the World Health Organization (WHO) indicate that by 2021, only 55 per cent of children were covered by one dose of measles vaccine (Democratic Republic of the Congo: WHO and UNICEF estimates of immunization coverage: 2021 revision). A minimum coverage of 95 per cent with two doses is recommended to prevent the spread of the disease.

“Some areas can only be reached by dugout canoe, or even on foot through the forest," says Alexis Mpesha, logistics manager for one of MSF's emergency teams in DRC. "It is not uncommon for our teams to be the only ones to reach certain villages because the local health authorities do not have the equipment, fuel or human resources to get there.”

For parents wishing to have their children vaccinated, the distance to a functioning health center, transportation costs and sometimes consultation fees can be discouraging. "Care is expensive and our resources are limited," says Anne Epalu, a native of Bangabola village, where MSF responded to a measles outbreak in 2022. "Some children die just because their parents don't have money to pay for treatment."

Boosting immunization is urgently needed

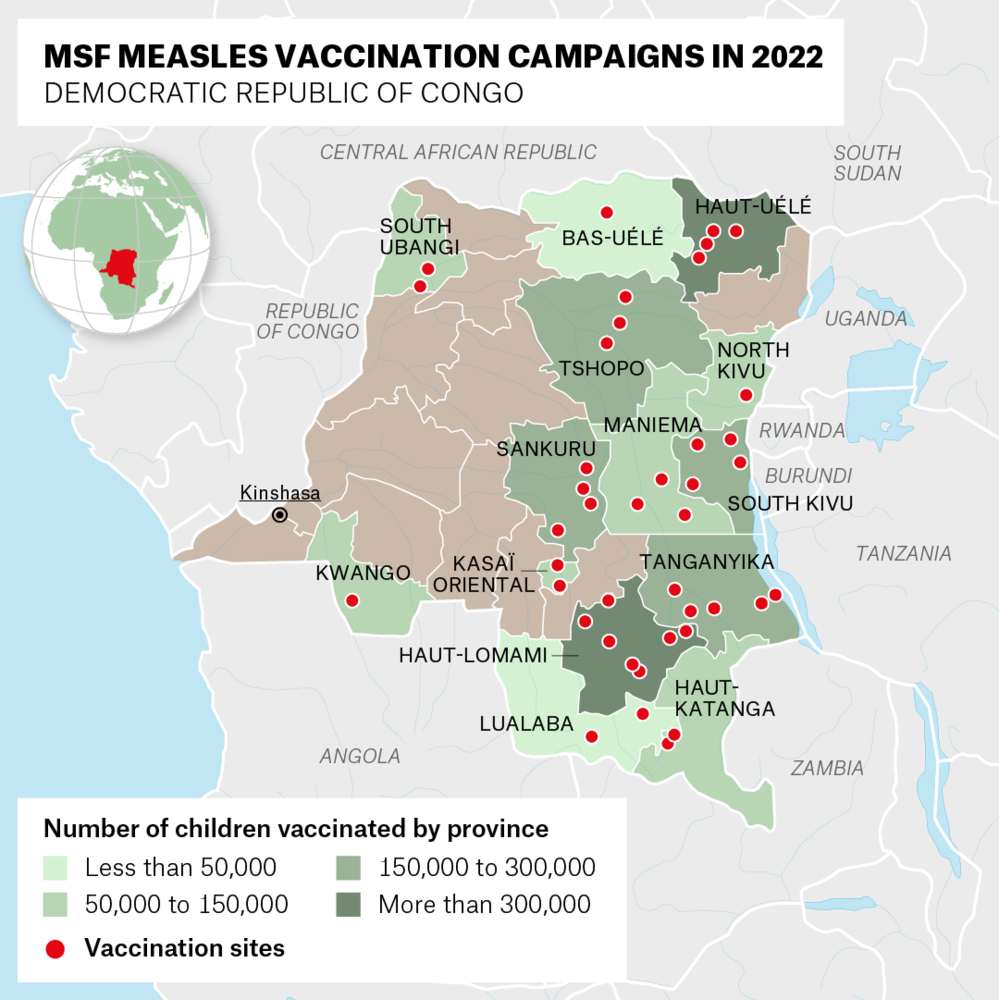

In 2022, MSF emergency teams in DRC vaccinated more than 2 million children in 14 provinces and treated over 37,000 patients with measles. MSF teams deploy in support of the Ministry of Health to organise vaccination campaigns and set up treatment units when a rapid increase in measles cases is reported in an area and local response capacity is limited or access is difficult. In addition to emergency interventions during outbreaks, MSF also provides logistical support for routine vaccination activities in health facilities in several provinces where its teams are present throughout the year.

But much greater efforts and investments are needed from the health authorities and their partners to increase immunization coverage in DRC and stop the endless cycle of epidemics.

"The implementation of the second dose in routine measles immunization activities needs to be accelerated," says Dr. Louis Massing. "This approach was recently adopted by the authorities and can make a real difference. Offering systematic catch-up vaccination activities during pediatric consultations in health facilities could also help increase significantly the immunization coverage in DRC.”

In the meantime, given the persistence of outbreaks in the country, which put more children at risk every day, it is essential to organize the mass catch-up vaccination campaigns that are planned since the end of 2022 without delay throughout the country.

“Meanwhile, our teams are committed to keep responding to measles flare-ups in DRC in support to the health authorities to the best of their ability. But to do so, it is essential that enough emergency vaccines are available in the country”, explains Dr Louis Massing.