Six months after numbers of children with measles surged, Dr Ei Ei Khaing, MSF clinical team leader in Taiz Houban mother and child hospital, describes efforts to tackle the life-threatening disease

“I have seen firsthand how the current surge in measles cases is affecting children in MSF’s hospital here in Taiz Houban in Yemen. Although measles is a preventable disease, vaccination coverage among children being treated for measles is just 16 percent. Once the virus spreads in the community, morbidity and mortality can be high, especially among young children.

Measles is endemic to the area where we work. In our mother and child hospital, we’re used to seeing an average of eight measles patients each month. But last June, the pattern began changing. Suddenly the numbers started to increase alarmingly, with children from many districts in Taiz governorate arriving at our hospital.

Soon the number of measles patients had doubled. We could not risk cross-contamination in our wards, so in late-August we decided to open a dedicated measles isolation unit. Six months later, the upsurge in measles cases shows no sign of abating and our efforts to address and contain the infection seem quite limited.

In the initial period, symptoms are easy to miss or misdiagnose. Up until the fourth day of contracting measles, the child exhibits flu-like symptoms: a fever, a cough, rhinitis, and a sore throat. After the fourth day, the child develops the infamous measles spots.

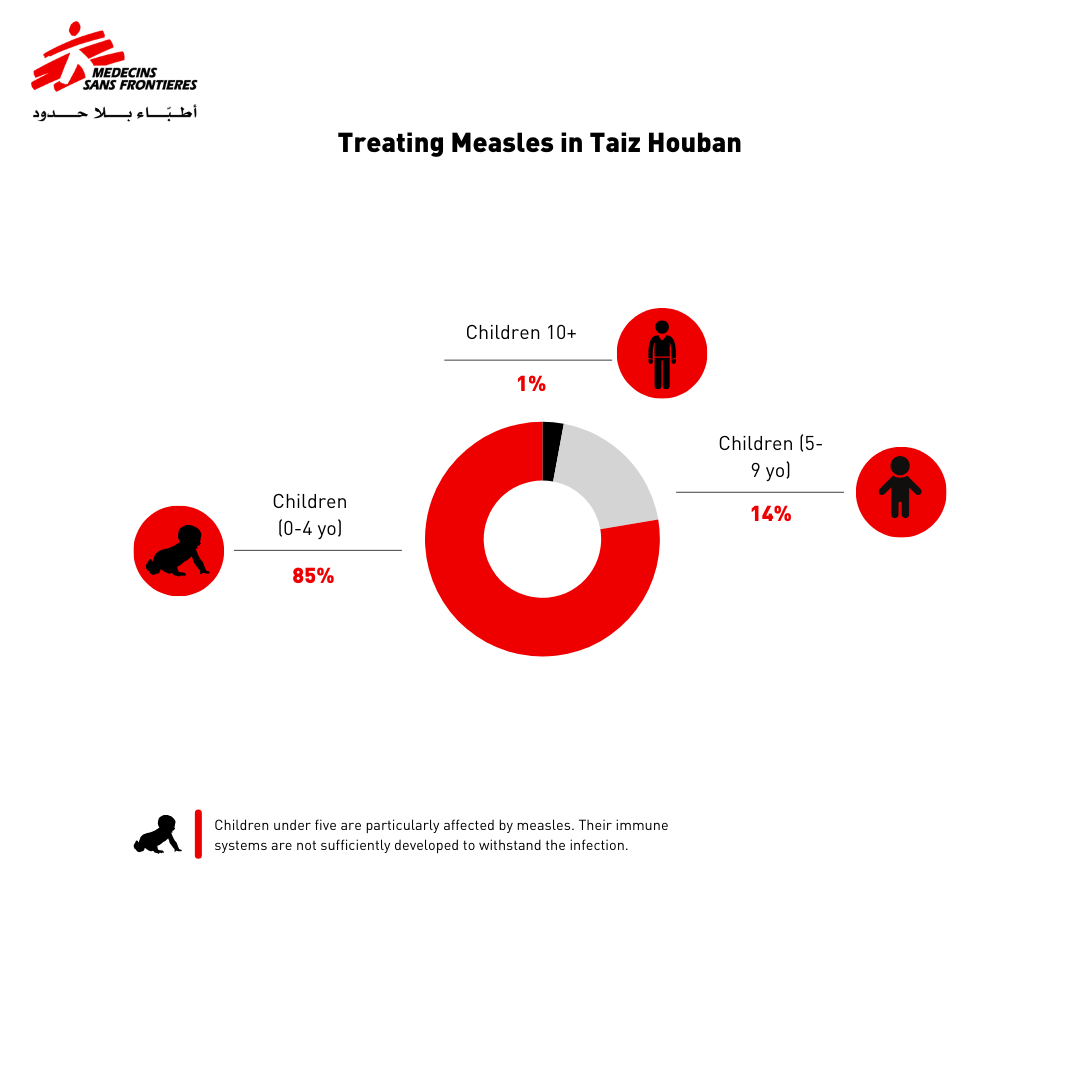

Children under five are particularly affected by measles since their immune systems are not sufficiently developed to withstand the infection. Once children contract measles, a temporary immunodepression causes measles-related infections such as pneumonia, conjunctivitis, inflammation of the ear and mouth, diarrhoea and swelling of the brain.

We receive many children with complicated cases of measles – more than I have ever experienced before in my life. There isn’t one simple reason for this.

People in Taiz, much like in the rest of Yemen, struggle to access healthcare. The nearly decade-long conflict in Yemen has had a devastating toll on the country’s health infrastructure; many health facilities are either non-functional or are ill-equipped to cater to people’s needs. Added to this, basic health services in public health facilities are costly for the majority of people, whose financial capacity is quite constrained.

The lack of primary healthcare services pushes caretakers to delay bringing their sick children to our hospital in the hope that the symptoms will resolve on their own with home remedies or medication from their local pharmacy, if they have one. In addition, the long distances people have to travel to get here serves as an additional constraint, since most can barely afford the transport costs.

Our hospital does not have an intensive care unit, so we refer patients who require mechanical ventilation to other hospitals. Sometimes caretakers tell me that they prefer to keep their children in our free-of-charge facility and leave the rest up to God’s will. Mohammad*, who is four-and-a-half, came to the hospital a week after developing a measles rash. He had encephalitis, one of the rare post-measles complications. His symptoms included a fever, disorientation and weakness in the lower body. Mohammad spent 15 days in the hospital, after which his symptoms resolved gradually and he could walk once again. Seeing patients improve and help relieve their suffering gives me such a feeling of usefulness.

Yet there are limitations to what we can do when patients arrive at our hospital late in their sickness. I will never forget Abdallah*, aged two-and-a-half, who was admitted to the measles unit at 7.30 pm one evening. He arrived with a rash, a fever and huge ulcers around his mouth and lips. We suspected he had contracted diphtheria on top of his measles infection.

By 11.30 pm, Abdallah was increasingly distressed and could not breathe well. At 12.30 am, he started to show signs of septic shock. We were preparing to transfer him to a governmental hospital where they treat diphtheria, but we worried that his body would not be able to handle the two-hour drive to get there.

At 3.30 am, he went into septic shock with signs of acute airway obstruction, so we intubated him to help him breathe better. Unfortunately, all these complications overwhelmed his body and Abdallah had a cardiopulmonary arrest. He did not survive. It shattered my heart.

Between August and December 2023, our measles unit received 1,332 children, 85 per cent of them under the age of four. In February 2024 alone, we received 220 measles patients. Our epidemiological projections do not foresee a decrease in patient admissions anytime soon. If the transmission of measles is not contained, children in this area will suffer a number of diseases that may become fatal if not properly treated in a timely manner.”

*Names have been changed to protect privacy.