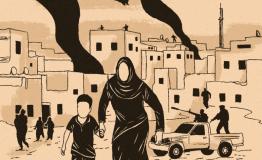

In a quiet corner of a displacement camp, a mother cradles her feverish child suffering from measles, her eyes filled with fear. She fled conflict to save her family, yet now she faces another deadly threat—one that could have been prevented with a simple vaccine. But access to routine immunization in conflict zones is anything but simple. For millions living in humanitarian crises, lifesaving vaccines remain out of reach, leaving children vulnerable to outbreaks of measles, diphtheria, and meningitis—diseases that should no longer be taking lives. Can you imagine the consequences? Preventable illness, unnecessary deaths, and communities trapped in cycles of health crises. We know how to stop it. There are clear, actionable steps that can save lives—if we have the will and resources to take them.

In conflict zones, bombs and bullets dominate the headlines, but vaccine-preventable diseases are killing just as many—if not more. Since 2020 when Covid-19 pandemic strike, global vaccination coverage has dropped sharply. In 2023 alone, 14.5 million children did not receive a single dose of routine vaccines, while another 21 million were under-immunized. In fragile and war-torn regions, where vaccination was already inadequate before the pandemic, the situation has only worsened. The results are devastating: for example, in 2022, over 300,000 measles cases and 6,000 deaths in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a polio outbreak in Gaza, and rising mortality rates from diseases we have long been able to prevent.

More than half of all unvaccinated children live in countries which are conflict-affected or with institutional or social fragility, where health systems are weakened or collapsing and access to basic medical care is disappearing. Global initiatives like Gavi´s Big Catch-Up aim to close the gap, but they do not adequately address the complex barriers that prevent vaccines from reaching those most in need. Political obstruction, logistical challenges, and inadequate funding continue to leave millions exposed.

South Sudan is a stark example of how conflict, weak health systems, and bureaucratic delays combine to create a perfect storm. Between the end of 2022 and March 2024, over 12,700 measles cases and 239 deaths were reported, a tragic but predictable outcome of systemic failures in outbreak response. Since 2023 the arrival of over a million refugees and returnees from Sudan has further overwhelmed an already fragile health system.

There are positive stories though. In Bulukat in Upper Nile, MSF’s mobile clinic provided healthcare to people displaced from Sudan, screening all new arrivals and referring individuals for vaccination. This intervention helped prevent outbreaks, but it also relied on a reliable supply of vaccines and the right equipment and logistics to keep vaccines cold, something that is hardly guaranteed in conflict zones.

In Yambio, in the Western Equatoria region of South Sudan, for example, a measles outbreak was declared in January 2024, but it took four months for a reactive vaccination campaign to begin. In that time, thousands of children fell seriously ill. The reason? Delays in securing vaccine supply and the reluctance of key health actors to act quickly. The outbreak could have been mitigated, but instead, lives were lost while negotiations dragged on.

The South Sudan experience reflects the broader failure of the international community to prioritize vaccination activities in crisis zones. The systems in place are too slow, too bureaucratic, and too detached from the urgency on the ground.

Let’s take Somalia’s Southwest State, particularly Baidoa, as another example of how conflict, displacement, and weak health systems fuel repeated outbreaks of preventable diseases. With over 700,000 internally displaced persons, Baidoa is Somalia’s second-largest IDP settlement. Despite a reported high vaccination coverage rate, cases of measles and whooping cough persist, with Bay Regional Hospital admitting nearly 6,000 measles patients between 2021 and 2023. Many new arrivals come from areas inaccessible for vaccination campaigns.

A mass vaccination campaign was planned in Baidoa in October 2023, targeting over 350,000 children for measles and 260,000 for pentavalent vaccines, which protect children from five diseases, including diphtheria, tetanus, and hepatitis B. However, despite agreement on the need and plan, the campaign never happened due to a lack of vaccine supply. In humanitarian crises like Baidoa, MSF and other actors are continually and repeatedly forced into a reactive approach, treating thousands of avoidable cases instead of preventing them.

We know outbreaks of preventable diseases continue to claim lives globally or that vaccination remains one of the most effective interventions to prevent illness and death. Yet, for people living in conflict and humanitarian settings, access to vaccines is still far from guaranteed. This is not because solutions don’t exist, but because systemic barriers, bureaucratic inertia, and supply failures persist.

Governments, donors, and global health actors need to take immediate, concrete action to ensure that vaccination and outbreak responses are rapid, effective, and equitable—especially in fragile and conflict-affected areas.

This requires financial mechanisms that allow flexible, needs-based funding in fragile settings, with pre agreements in place to enable rapid outbreak response and quick access to vaccines and facilitating swift engagement from different health actors. Providing vaccines to more children by extending the age range up to at least age five on a permanent basis, is also critically needed. At the same time, governments and health authorities also have a role to play in eliminating bureaucratic barriers hindering vaccination in conflict zones and ensuring accountability for the quality of responses.

Ultimately, this is not just about funding or logistics—it is a matter of political will. Without urgent action, history will continue to repeat itself, and the world will once again stand by as preventable disease outbreaks devastate vulnerable communities.