Sudan

The war in Sudan has had disastrous consequences for people’s health and wellbeing. Throughout 2024, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) delivered medical and humanitarian assistance across many of the country’s conflict-ravaged states.

The fighting between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and Rapid Support Forces (RSF) has caused the world’s largest displacement crisis, in which millions of people have been driven from their homes. Many have been subjected to ethnically motivated and sexual violence, and are facing malnutrition, as well as the loss of their homes and livelihoods. People’s suffering was compounded in the country’s eastern and central states by outbreaks of cholera, and spikes in malaria and dengue, fever during the year.

Our activities in 2024

Data and information for the 2024 International Activity Report

1,061,200

1,061,2

205,800

205,8

191,300

191,3

113,600

113,6

39,700

39,7

21,500

21,5

20,400

20,4

11,300

11,3

10,700

10,7

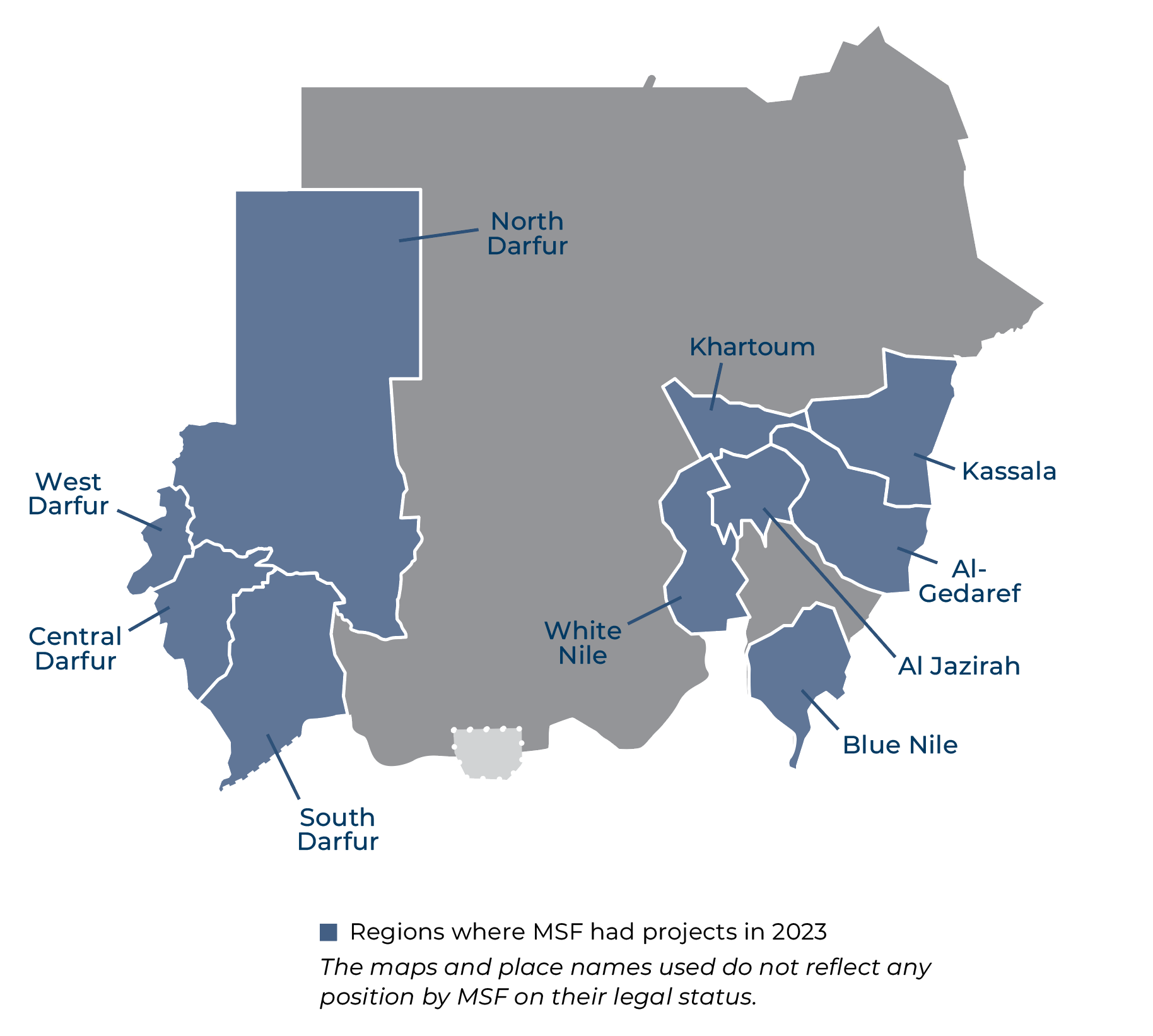

MSF in Sudan 2024

Map of the areas MSF worked in 2024

Refugee, migration and displacement

Article

4 Mar 2026

War and conflict

Sudan: Repeated drone strikes hit civilian areas, MSF treats around 170 people in two weeks

Article

19 Feb 2026

Access to Healthcare

Measles vaccination campaign in El Geneina: The first since 2021

Article

7 Feb 2026

War and conflict

Sudan: MSF visit to El Fasher finds a largely destroyed and emptied city

Article

28 Jan 2026

Conflict in Sudan

Access Restrictions are Preventing Lifesaving Medical Care in Jonglei State

Article

16 Jan 2026

War and conflict

In the Midst of War: How Sudanese Colleagues Continue to Save Lives

Article

13 Jan 2026