“Makhanga area, which is very fertile, is home to around 18,000 people who rear cattle and grow crops like maize and rice. It is low and flat and surrounded by the Shire River and its largest tributary, the Ruo, so it basically looks like an island,” says Labana. “This makes it very prone to flooding. If there are rains in nearby Mulanje district or upstream in the City of Blantyre, and the Ruo swells, then the area is at risk. If there are rains upcountry and the Mwanza River swells, it can cause the Shire river to spill and the entire area is at risk. Heavy rains starting in early March affected all the southern districts, so the entire area has been largely submerged for weeks,” he says.

Learning from previous floods

The lessons Labana learned in responding to the previous severe flooding in Makhanga area in 2008 and 2015 are serving MSF’s current emergency response efforts. “In 2015 we mapped the most risky, flood-prone areas in order to focus our response, and identified people to work with closely in the community,” he says, adding that these relationships have enabled MSF to come in quickly, when the heavy rains were just starting, to assess the situation and plan an immediate response with the community, who already had some experience of how to distribute relief items.

“In our previous flooding responses we shared information on how to find and prioritise people who needed medical care. In 2015, a lot of people died in this area, but this year fewer lives have been lost to the flooding, partly because people now know where to find higher ground,” he says.

Makhanga health centre was severely flooded, but Labana says MSF experience of responding to previous floods again proved helpful. “In 2015, a lot of drugs were soaked in floodwater, ruining them. Afterwards MSF raised the height of the shelves so that the drugs would be safe from the water, so this time the stocks were spared,” he says.

Shortages of food and clean water

Fewer lives have been lost in the 2019 floods but the damage caused to homes and crops has been immense. “It isn’t just crops that have been lost, it’s also food stored in homes in an area that was in need of food support even before it was flooded. The floods have contributed to great hunger already in the area,” says Labana.

The flood waters have also submerged boreholes and destroyed toilets, and with thousands having to defecate in the open the risk of waterborne diseases such as diarrhoea and cholera breaking out is high. Labana says the area’s many swamps are breeding grounds for mosquitos, putting people at risk of contracting malaria. “People here are vulnerable in terms of their health right now, with many sleeping outdoors or in their chicken coops, because their homes were destroyed,” says Labana.

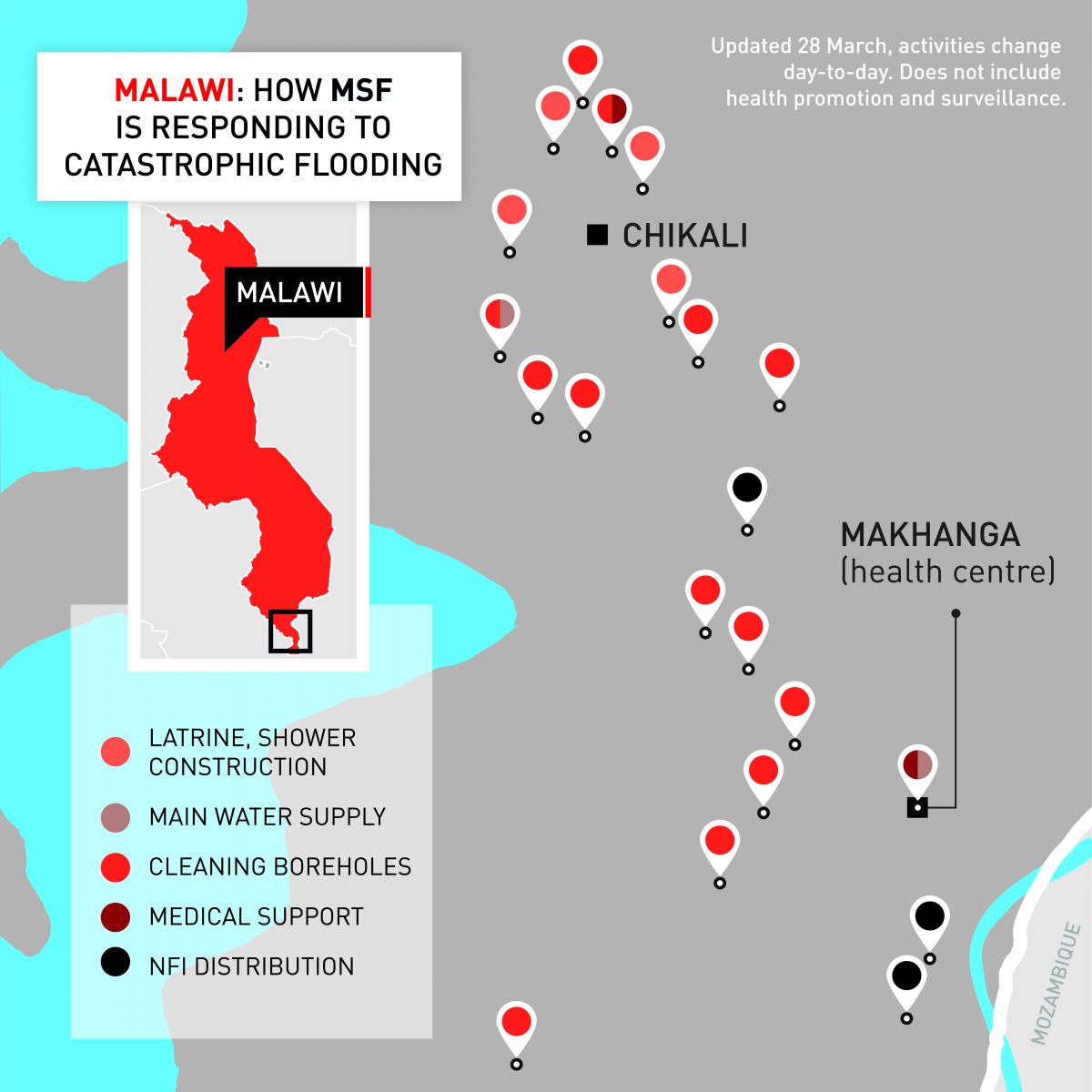

The borehole at Makhanga health centre was contaminated by the floodwaters but MSF staff have managed to clean it and ensure that the water is safer to use. Elsewhere, MSF’s water and sanitation teams have been distributing chlorine, cleaning water points, and constructing toilets and showers. “Our main concern is that we prevent an outbreak of diarrheal diseases and cholera,” Labana says.

Challenges getting medical care

The flooding in Makhanga has pushed most of the district’s health workers to higher ground in the north for safety reasons, leaving the few remaining health workers under severe pressure. “In the beginning there was just one Ministry of health medical assistant and one hospital attendant. To support them, two MSF staff are providing basic healthcare, HIV services and disease surveillance, with approximately 150 consultations per day. We’re now seeing a lot of respiratory infections and malaria,” Labana says.

Working with the Malawian District Health Office, the MSF medical team has done an outreach clinic to ensure access to primary health care services and to drugs for patients with chronic diseases, including HIV and tuberculosis, who lost their medications in the floods.

“MSF is providing healthcare, water and sanitation and distributing essential relief items and hygiene kits, but our wish is to see more organisations responding in areas that we cannot manage, such as food. Looking ahead, the community of Makhanga is really going to need more support,” says Labana.

In the flood-affected regions of southern Malawi, the rains that started in early March - have now largely stopped and access to the flooded areas is improving. To date, flooding has caused 59 deaths, 677 injuries, and the displacement of around 87,000 people in camps overall (OCHA, 22 March). One of the worst affected area is Makhanga area, which essentially remains an island cut off from all road access, though it has electricity again. While many thousands of people are currently sheltering in schools, churches and makeshift camps for displaced people, some are starting to return home to rebuild their houses. There has been widespread destruction of agriculture and animals – an estimated 50 percent of the area’s crops may have been lost. An MSF team of 18 people is currently working with local authorities, communities and the health ministry to cover the needs of an estimated 18,000 people in Makhanga with health, sanitation and non-food-item supplies.