Elena Graglia

Medical coordinator for the MSF project in Roraima

After being closed for several months due to the COVID-19 pandemic, last June the Brazilian government authorised a partial opening of its border with Venezuela. From that moment on, “the exceptional admission in Brazilian territory, for humanitarian reasons, of Venezuelans and Venezuelan residents who are affected by the crisis in Venezuela” was allowed, as well as “the regularization of Venezuelans and Venezuelan residents who arrived irregularly in Brazil during the pandemic, meaning from March, 18th, 2020 on”.

While things seemed to be quite simple on paper, the daily reality for those migrants remains very worrying: until the end of 2021, thousands of Venezuelans lived on the streets of the Brazilian northern state of Roraima, facing major barriers to access healthcare and other basic services.

Although by the beginning of 2022 most of them were able to find some kind of accommodation, either at informal occupations or at official shelters who had their capacity increased, their condition remains precarious. What could be seem as an improvement also reflects the fear of violence migrants may face if they stay on the streets. That´s why most of them choose not to circulate out of the shelters, and this has been reflected in a smaller demand for health services at public facilities during last December.

Pacaraima, a town of 20,000 inhabitants in the north of Roraima, is the first place of arrival for hundreds of Venezuelans who cross the border into Brazil daily with the hope of finding a better life and safety for them and their families. At the peak of the migration so far, between October and November last year, 500 people made the journey through improvised paths called las trochas (‘the trails’ in English) everyday, while the migration office at the small border town could only process requests for legal status for 65 people.

In November, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), more than 3,000 people were living on the streets in Pacaraima while waiting for their legal status to be cleared, due to the lack of shelters. The figure is no less than 15% of the town´s population, which helps us to realize the dimension of the issue.

Starting in December, the streets became almost empty, with the migrants looking for shelter while fearing for their safety, afraid of violence. Additionally, with the proximity of the Holiday season, movement at the border was reduced, as it usually happens during this time of the year. In the following months we hope to have a clearer picture and we are getting ready for a possible rise in the demand for our services.

We see that people cross the border with high hopes, but once they get here, most of them have to face a harsh reality. They usually stay in Pacaraima until they are able to clear their migration status, which can be a slow process. The town’s health system is precarious and there are not enough resources to provide adequate healthcare.

According to Brazilian law, everyone has the right to access public health services, no matter at what stage their migration status and process is. But the reality is that even with this formal right, the actual services are overcrowded and limited in Roraima state.

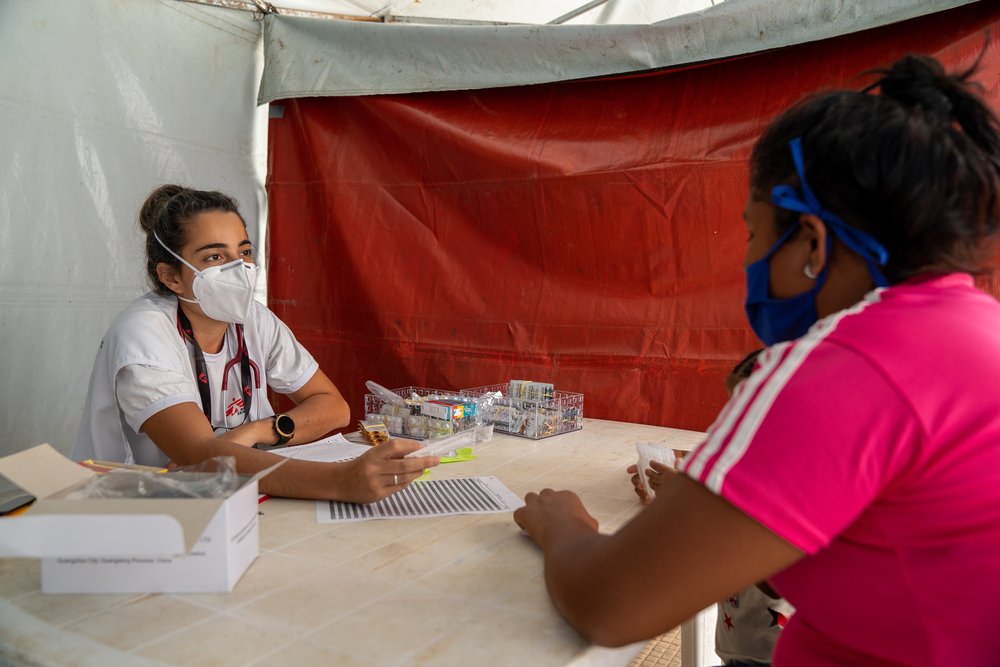

In response to the gap in health services and access to information, MSF has established medical, sexual and reproductive health and mental health services through mobile clinics in Pacaraima and Boa Vista, Roraima’s state capital. From January to October 2021, MSF teams provided care to 37,517 patients across all of our services in both locations.

From July through to the end of September, teams cared for 14,551 patients, and 56 per cent of the total number of consultations in the first nine months of the year were done during those three months, when the border was already partially opened. The main reasons for consultations were respiratory tract and gynaecological infections.

Meanwhile, the mental health team identified that 69 per cent of patients had symptoms of acute stress, depression and anxiety. The main causes were displacement, family separation, walking long distances and experiencing violence.

When people arrive and see us, the first thing they ask us is about the health services we offer and how to access them. They arrive at a country with a different culture and language and have to face multiple barriers.

We explain to them how to access the public health services network in Brazil that despite being overwhelmed by the high demand, should be available to them. MSF also conducts health promotion activities focusing on messages about sexual and reproductive health.

“When I arrived in Brazil two years ago, there was not as many people here as there are today,” says Alejandra*, an MSF patient told us. “The services I used to access when I first arrived, such as getting a doctor’s appointment, are not available today. The only health service I have is this clinic.”

“I was able to bring my daughter from Venezuela a couple of months ago, but her migration status is still not completed, and every time we go to see how her process is, the office is always full”, she explained us.

But even with the extremely precarious situation in Pacaraima, migrants and asylum seekers are almost unanimous on saying that they’d rather be homeless in Brazil than stay in Venezuela.

“When I got here, I was sleeping on the floor, on a cardboard box, but even so, it’s better than in Venezuela,” says Alejandra.

Our patients tell us that migrating wasn’t part of their life plan, and even consider it a last resort to escape from the financial, social and food insecurity in their homeland. And all of them tell us that they faced hunger and danger during the journey that brought them here. Some weeks ago, a boy who was participating in a mental health session made a drawing of a street. We asked him why and he simply answered that he had travelled for many weeks, walking or hitchhiking, but always on the street. It certainly had a huge impact on him.

All the stories we hear, although in many times express some hope, show the hardships of everyday situations they had to face on their journey. And their present lives, living in a precarious situation and waiting for their legal situation to be cleared, are not simple either.

*name has been changed