MSF neonatology team tackles challenges of the Rohingya humanitarian crisis while saving newborns

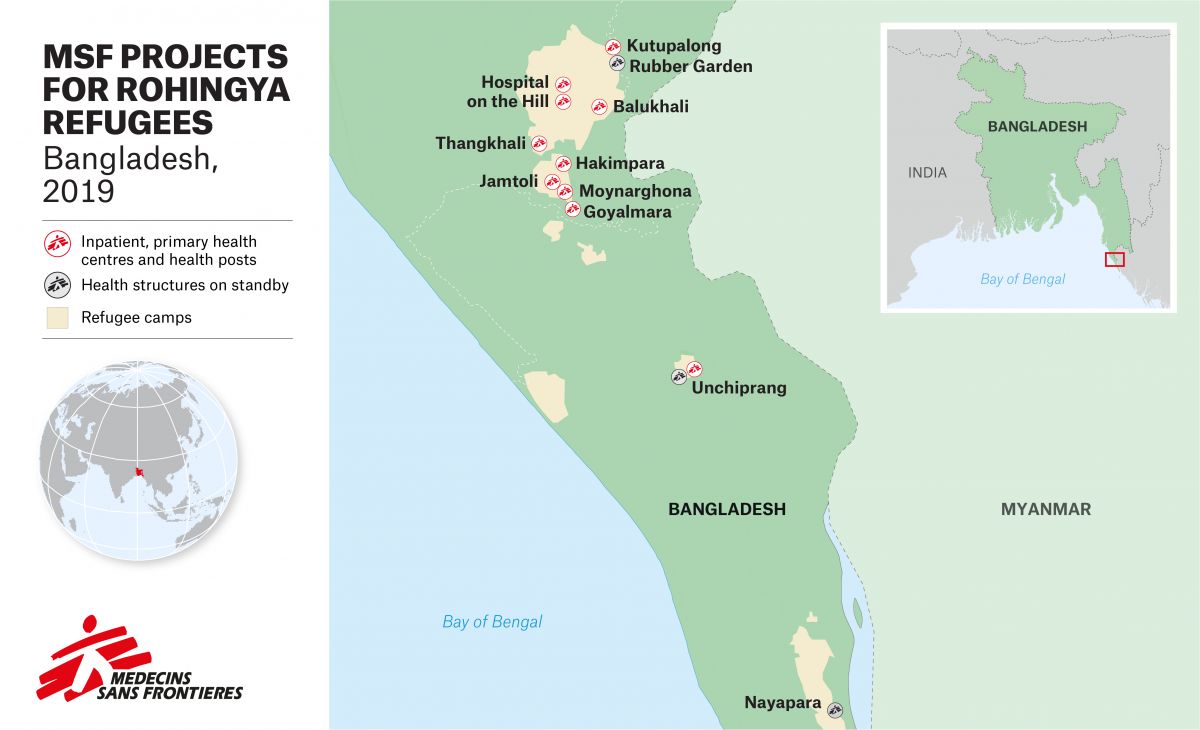

Gaziur abruptly leaves a conversation and a cup of well-deserved tea. Holding a phone to his ear, he mouths “sorry” and rushes off into the neonatal ward of MSF’s Goyalmara Green Roof hospital in Ukhia, Bangladesh. Surrounded by paddy fields, elevated mud tracks and bamboo huts covered with thatched roofs, this specialised hospital sees a particular category of Rohingya and Bangladeshi patients: mothers and children.

Inside the neonatal intensive care unit, a newborn baby, only days old, is struggling to breathe. Nurse supervisor Gaziur Rahman and his colleagues get to work. Standing nearby, the baby’s young Rohingya parents have a shocked look in their eyes. They haven’t even had a chance to name the infant girl. Gaziur is helped by a team of nurses who take turns carrying out bag-valve mask ventilation – a method of squeezing a bag to help a baby breathe oxygen into its body. A digital pulse oximeter displays the baby’s heartrate and blood oxygen levels; the reading of 60 to 70 percent oxygen level does not augur well.

None of the nurses is breaking a sweat, but they do not look satisfied. A doctor is watching the proceedings and taking notes. Ten minutes have passed. Gaziur looks determined, but does not want to raise false hope for the baby’s parents. This is going to be a tough night for the MSF team. Gaziur speaks softly: “The prognosis does not look good.”

Forty km away in Cox’s Bazar town, MSF medical coordinator Jessica Patti has her own challenge. It is not enough to open a hospital and wait for the patients to arrive. MSF staff have been increasing their efforts to raise awareness of the hospital amongst other humanitarian organisations.

“The first 28 days for newborns are critical – they need both preventive and curative medical care,” says Patti. “Unfortunately, lack of healthcare facilities for both refugees and Bangladeshi citizens can mean newborns are extremely susceptible to death in their first month. We opened Goyalmara hospital to focus on neonatal and paediatric care, and we want unwell newborns to be referred here from other hospitals in order to receive specialised care.”

Easing access to specialised care

Referral pathways are critical in saving lives. Take eclampsia, a condition in which a pregnant mother suffering from high blood pressure gets convulsions which can prove deadly to both mother and child. Rohingya women prefer to give birth in the private spaces of their house, facilitated by trusted traditional birth attendants. The time taken to travel from the closed, cramped spaces of Rohingya camps to a basic health outpost and then on to a dedicated maternity hospital can mean the difference between survival and death for both mother and newborn. If patients are transferred directly to Goyalmara from other health facilities, says Patti, more lives will be saved.

Back in the neonatal intensive care unit, there is an improvement. The oximeter shows increased levels of oxygen in the newborn’s blood, a sign that her condition may stabilise. Gaziur rubs the palm-sized chest of the baby. Her body is showing signs of movement, a noticeable change from when she seemed lifeless 15 minutes ago. The next milestone for the team of medical staff and the family will be for the newborn to breathe spontaneously and unassisted. The baby's mother is teary-eyed, and the father is pacing outside the ward.

The time-window for survival for this baby is closing fast. Bag-mask valve ventilation can prolong a newborn’s life, but unless the baby can breathe unassisted, the resulting flow of oxygen can cause neurological problems and ultimately death. If there is no improvement in the baby’s condition, the team will have to end resuscitation and sensitively explain the outcome of a likely death to the family. For Rohingya families who have experienced violent and traumatic events in their flight from Myanmar to Bangladesh, losing yet another relative can take an unimaginable mental toll.

The safety of refugee camps in Bangladesh is not a guarantee for survival for numerous Rohingya babies. From the relative calm of a mother’s womb to being born in unsanitary and crowded conditions in the camps, a refugee neonate’s chances of survival depend on escaping circumstances ubiquitous in humanitarian emergencies. The Rohingyas were deprived of healthcare services in Myanmar; even today many of our Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh are unable to get appropriate medical care until it is too late.

Reasons for this can include traditional practices of the community, lack of trust in unfamiliar health facilities and difficulties in moving within and outside the camp; humanitarian organisations need to do more to understand the barriers to care and health-seeking behaviour of the Rohingya. There is also a need to increase access to specialised healthcare facilities like Goyalmara hospital.

In the neonatal ward, the baby shows signs of improvement. Unlike a child or adult, a neonate cannot express pain or relief. Medical staff have to look for visual cues such as skin colour, squeezing of eyes and hand movements to ascertain if a baby is suffering or improving and to manage any pain. There is palpable optimism in the intensive care unit as the Rohingya baby’s arms move upwards, fists clenched, as if to show signs of readiness for a fight. Gaziur and his team of nurses continue to pump the oxygen bag.

MSF’s Goyalmara Green Roof hospital is a specialised facility for neonates, paediatrics and maternity care. The hospital has neonatal and paediatric wards with dedicated intensive care facilities, a maternity ward, an outpatient department and an emergency room for all adults. We also run a comprehensive mental healthcare programme for children and adults, outreach and health promotion activities. Since October 2018, the hospital has admitted 217 newborns and 247 children for neonatal and paediatric care, and admitted 348 patients to the maternity ward with assistance of 127 deliveries.